ENO revives Jonathan Miller’s 1986 Mikado

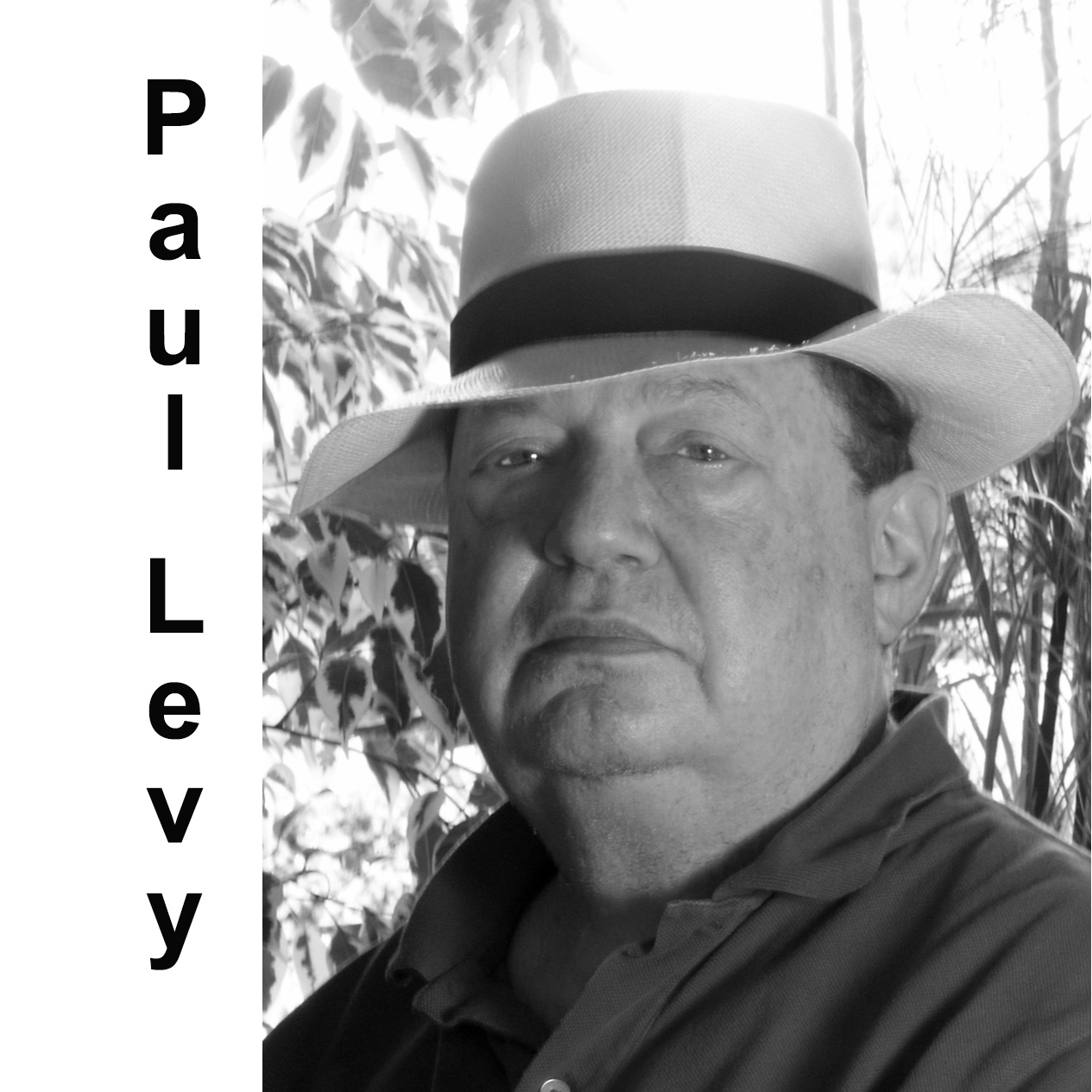

<image001.jpg>Sir John Tomlinson as the Mikado photo by Genivieve Girling

<image001.jpg>Sir John Tomlinson as the Mikado photo by Genivieve Girling

Despite some newsworthy casting, there don’t seem to have been many reviews of the current revival of Sir Jonathan Miller’s bankable production of Gilbert and Sullivan’s The Mikado at the English National Opera. Which is a little odd, because the title part of the emperor of Japan is being sung by Sir John Tomlinson. It is the 50th operatic role sung by this most celebrated Wagnerian superstar, probably the greatest Wotan of our lifetimes – oh, and Hagen, Holländer, Gurnemanz and Hans Sachs. In Stefanos Lazaridis’s all white, Sybil Colefaxy, 1920s Mayfair Grand Hotel staging, Sir John is costumed (by Sue Blane) in an elephantine fat-suit, with a red silk handkerchief waving out of the pocket of his snowy white suit, looking like a relatively jolly Sidney Greenstreet in The Maltese Falcon.

Miller’s production was premièred at ENO in 1986, and Ko-Ko, the Lord High Executioner, seems to have been sung by baritone Richard Suart in most of the revivals. This year his “Little List” includes nearly every prominent, if not eminent politician in the coming election, starting with the shameful, immediate ex-Cabinet, and zooming in on “Bo-Jo”, of course, but trumped by a gleeful bad word for the Donald. (“Narcissist” is such a useful rhyme for “list.”) The list of the condemned is changed for each revival, and I imagine 2019 will see many changes of those (who will none of them be missed) during the run.

Resisting vainly the acute temptation to pun that the production has been shored up by another star, let’s just say that the great comic baritone, Andrew Shore, sings Pooh-Bah, Lord High Everything Else to Ko-Ko’s Lord High Executioner. Pooh-Bah’s tracing of his genealogy to a single-celled organism is Gilbert’s stunning reminder that he was a woke Victorian intellectual and knew his Darwin and Huxley.

The roster of names we ought to have known before entering the Coliseum to see this hundred-and-somethingth performance of Sir Jonathan Miller’s Mikado, concludes with mezzo Yvonne Howard as a steely and funny Katisha.

The best singing of the night comes, unsurprisingly, from the young lovers, both ENO Harewood Artists, tenor Elgan Llÿr Thomas as Nanki-Poo and soprano Soraya Mafi as Yum-Yum. Her rendition of “The Sun Whose Rays Are All Ablaze” made me wonder why this ballad hasn’t been covered by every good singer of our own times – but then I reflected that it probably does take an operatic soprano with more than a hint of spinto to belt it out.

In the interval I shared a glass of pinot grigio with the celebrated stage, screen and TV star, Anita Gillette, who pointed out how difficult the work is to perform, especially given its speed. Conductor Chris Hopkins didn’t help the huge chorus much, as his tempi sometimes didn’t allow them to cram in all the syllables Gilbert wrote for a single phrase of Sullivan’s.

It’s amusing to think how little was known of Japanese music when the piece debuted in 1885, which accounts for the eclecticism of Sullivan’s score, I suppose. There is something both awesome and weird about a score that can incorporate the tune of the Japanese marching song “Miya sama,” and also what sounds to me like an American hoe-down. “Miya sama!” “Yee haw!”

Though the second half was fizzier than the first, what I enjoyed particularly about this lavish staging was the dancing. The dozen or so boys and girls who trade their parlour-maid’s high heels and bell-boys’ footwear for tap shoes in Busby Berkeley-like formations gave me a thrill, thanks to Anthony van Laast’s original choreography and Carol Grant’s revival of it. If you haven’t seen this ancient, classic production – or haven’t seen a revival of it for the past 20 years, you owe yourself the chance at least to see the stunning sets, costumes and choreography. Even if G & S is not your thing, this one is a cultural milestone; and its ticket sales will help to put the ENO onto a more sensible path, such as giving up the nonsense about not singing operas in their original languages. If it weren’t for the English surtitles, after all, though sung in English, the audience could not possibly follow all of Gilbert’s densely-worded lyrics.

The hero of the evening, though, is Private Eye’s beloved Dr Jonathan, Sir Jonathan Miller, whose direction (here revived by Elaine Tyler-Hall) is the source of the treasure-hoard that has allowed ENO’s survival for most of my opera-going life. It is no exaggeration to say that everyone on the stage – and there were sometimes dozens – knew exactly where he or she was to stand, look, gesture or sing and to whom, at every moment he or she was on stage. Detailed direction of this sort, of course, evolves into or from the choreography as well as from the score. Miller is a genius at grouping the players on the stage – just think of his ENO Rigoletto, where the knots of people are eye-catchingly interesting, without actually distracting attention from the principal action on stage.

If I have ever written anything worth reading about the performing arts, it is because I was lucky enough to witness Miller in action (years ago), leading a workshop to teach young opera singers about acting. In a very few hours he changed their careers (and educated me) by elucidating the simple first principles of drama and psychology. It all boils down to the director making certain that when a character speaks (or sings) to another character (or group of characters) he actually addresses that person or ensemble, and (if possible) makes eye contact. Words or lyrics are almost always spoken or sung to someone else on the stage, and relatively rarely to the audience, which is a consequence of their meaning. The director who remembers and enforces this can make a dramatic silk purse out of almost any old sow’s ear, and, in doing so, pays homage to Sir Jonathan Miller, the best and finest British director of the age.